By Tim Briedis:

“To be truly radical is to make hope possible, rather than despair convincing” – Raymond Williams.

At about 2pm, on Wednesday October 27th 1999 at the University of Western Sydney’s (UWS) Macarthur-Bankstown campus, around a hundred students began an occupation of the university’s Student Centre. Lasting for 14 days, until midday on November 10th, it was the longest occupation of a university admin building in NSW in the 90s. Eventually, the university admitted defeat, signing a 6 page agreement with the occupiers that conceded to 27 demands. The activists had run a union-style ‘Log of Claims’ campaign, in which they surveyed as many students as possible, investigating what students thought the main problems with the university were, which were then drawn together into a series of demands. They ranged from capping tutorial sizes at 25 (the first such cap in Australia), a guarantee that new library fines and proposed fees around car parking and printing be scrapped, better access to printing and computer facilities, improved security and disability services, better conditions for international students, a pledge that no staff be sacked over the holidays, to installing condom and tampon dispensers in the toilets. To put the occupation in context, Pru Wirth – a prominent student activist in Sydney in the 90s – recalled that:

A fourteen day student occupation was pretty much unheard of. So UTS was around 24 hours, Sydney Uni I don’t think was even that… A fourteen day occupation is crazy! So people saw this success at Bankstown and thought ‘we want to replicate that’

Beyond its length, why should we care today? First – amidst narratives of campus quietude and apathy – it helps show the possibility of something different, in an era not too far removed from our own. Second, although histories of radical politics can never provide straightforward and simplistic lessons for activists, they can offer a ‘useable archive’, complementing a toolbox of possible tactics and strategies. To follow the author and historian Kristin Ross one can therefore think about history as: belonging to the past, and as a kind of opening up, in the midst of our current struggles, of the field of possible futures.

This article is in this spirit. Although the demands of the occupiers were only won temporarily, I argue that the Bankstown campaign highlighted a different way of doing activism, with an imaginative strategy for building and publicising it and a democratic, participatory process emphasised. This collective decision-making – as opposed to a committee of politicised students separate from the student body deciding on a list of demands on their own – was vital. Michael Thorn, a UWS student and participant in the occupation, recalled that the Log of Claims was:

just people getting blank sheets and filling out what they hated about the uni … The important thing was that it was all pulled together, and that it was done justice. Once pulled together you have a log of claims that was expressing exactly what people were saying. You could very easily change it around, change the wording and make it sound different. I think because of that students at Bankstown felt a sense of ownership over the action.

But beyond this the occupation itself was an extraordinarily radicalising, exhilarating and galvanising event for those involved. In order to situate Bankstown within a continuum of protest, it helps to conceive of it as a ‘moment of excess’: a term coined by the UK-based collective The Free Association, that describe moments in which capitalist normality is broken, alternative ways of living are experimented with and where:

“time accelerates, creativity is amplified and the space of what is possible expands: everything appears to be up for grabs”

When we charged in to the admin building, remembered Thorn, ‘that was the moment that radicalised me’. For Andrew Viller, the Education Officer at the Students Association at the beginning of the occupation, the level of solidarity and camaraderie revealed ‘glimpses of another world … a very communal existence, a very communist existence’. After the occupation, Viller recalls, even though they’d won people felt:

quite sad, as the space no longer existed. Um, I remember very clearly having conversations with people I didn’t know prior to the occupation, we’d become almost like family. And we were sitting around having a coffee and smoking some cigarettes and this student said ‘what do we do now? I just don’t want to go back to regular life’.

Yet it also left a mark beyond the immediate event. The sense of excess generated by the occupation spilled over and was pivotal in catalysing activism at UWS for several years afterwards. Students played a vital part in supporting workers at the nearby Mirotone paint factory in a lock-out in 2001, and in the same year, they occupied Goolangullia, the Aboriginal education space at uni, for 52 days, preventing its closure.

‘Are you pissed off about this Uni?’: origins of the campaign

The campaign came from humble beginnings. While there were some activists on campus, at the start of 1999 there was only a very small group. Yet despite this, because they were the only organised political faction on campus they had won left control over the SRC – giving them access to resources and a monopoly over the office-bearer positions.

That year left-wing activist Nick Harrigan was the NUS NSW Education Officer, a half time paid office-bearer position with a salary of $12,500. Through his position, Harrigan was able to provide support to some of the key Bankstown students. He was in contact with Viller and during the mid-semester break the two of them met up and wrote a timetable for a Log of Claims campaign. One influence was the US ‘organiser model’ for trade unions, which stressed concrete, winnable demands. This sort of planning became entwined with a more spontaneous outburst of anger from a group of Social Work students. Both Karen Hooper and Amy McMurtrie, social work students on campus, remember a tutorial in late August in which the class started talking about the numerous problems that they faced on campus. Their lecturer suggested that they go to the Students’ Association about them and try and do something, and five students went as a group.

Upon arriving, they found that their grievances fitted in perfectly with the campaign that had been planned. After this, the first meeting of the Education and Welfare Collective was called. The first few meetings were attended by 10-12 students, quickly growing to 20-25. By the week of September 13th, members of the collective began distributing Log of Claims surveys around the campus. Posters asked:

Are you pissed off about this Uni?

Do you have an overcrowded tute?

Are you pissed off about the car park fee being introduced?

Have you been fucked around by Admin?

Are you not finding this place all it was cracked up to be?

John Mcguire, the Welfare Officer for the year, remembered that although he’d had difficulty leafleting for events and meetings the semester before, once they started using the Log of Claims it became much easier to get people interested as:

this was saying to people ‘we don’t know what the issues are’, you should write them down and tell us … that definitely changed the dynamic, people were interested, people were excited, I remember hearing people talk about it, I remember people talking about it to us, people we didn’t know

The way in which the Students Association was structured was also important. Instead of just focusing on activism, they also ran the bar, food outlets and even put on a weekly trivia night. Even though this wasn’t explicitly political, it meant that they were known on campus, which made it much easier to communicate to students.

Perhaps the most effective strategy was the use of an informal class delegate system. Collective members became organisers in their own classrooms, encouraging their classmates to fill out the surveys, similarly building on pre-existing networks of commonality and trust. After about three weeks of distribution, they had collected several hundred surveys – an impressive tally out of a campus of 3000. After collating the surveys, they narrowed the list of grievances and a rally was called for Wednesday October 20.

The activists promoted the rally for about a week and a half beforehand, and on the day about 250 students turned up outside the library. The final speaker urged them to occupy and the crowd surged towards the admin centre. However, security got wind of what was going on and were able to move in and lock the doors. Undeterred, the activists decided to stay put in the middle of the main building – the central site in which every student had to go through. They received word that Deputy Vice-Chancellor David Barr was going to address the group, so they set up a stage and an open mike and people got up to talk about their problems at the university.

After about three hours, Barr made an entrance. Barr and the students began to debate the list of demands. Eventually a proposal was passed in which Barr agreed to have responded to all of the demands after a week. A demonstration, billed as ‘The Students vs David Barr’ would be held the following Wednesday, October 27 which Barr pledged to attend.

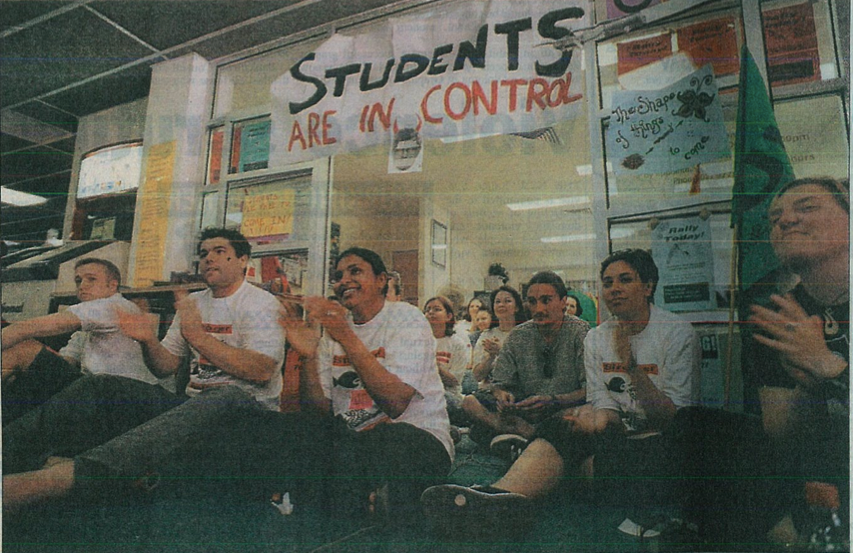

Yet on the day of the rally it soon became clear that Barr’s pledge meant little. After about thirty minutes the 300 or so activists decided they’d had enough waiting and moved into the main building. They had sent two students inside earlier to prevent any attempt to lock the Student Centre, and they spotted that the doors were still open. They moved inside and the occupation had begun.

‘UWS Macarthur under Student Control!’: The occupation begins

The students quickly divided themselves into collectives based around particular needs -such as food, bedding, building and communications. Even a fun collective was formed! Conveniently, the Students Association was located only about 100 metres away from the space. This meant that it was very easy for students to go there and print off posters and leaflets supporting the occupation, and the campus and its immediate surrounds were soon flooded with propaganda. The main university sign at the entrance to campus was re-decorated to say ‘UWS Macarthur Under Student Control!’ Stickers declaring ‘Against staff cuts? Join the occupation’, ‘Students united will never be defeated!!’ and later ‘You won’t believe how many people I’ve slept with in the last week’ began to proliferate. A website was set up that took particular glee at mocking university management. It included a picture of the Vice Chancellor that you could mouse over and he would say things like ‘I am Conan the Destroyer and I will crush you’!

Barr rapidly became a hate figure for the occupiers. Posters mocked his non-appearance at the demonstration, with one reading ‘Come out David Barr, come out David Barr, come out come out wherever you are’. A cut-out Barr mask was designed, with text reading ‘Liar’ on his forehead and optional bright red horns. Later, the occupiers even went to a Campbelltown campus meeting of university admin, and taped posters of Barr’s face looking in at them.

The occupation soon drew in students well beyond the usual activist circles, and even a group of policing students joined the occupation. A few of them had completed their internship at Bankstown Police Station, and were on a first-name basis with the local cops. They were in contact with people on the inside, and were able to provide intelligence to the occupiers when it looked like the cops might be coming to evict them. When the police showed up outside Bankstown campus on the first Friday of the occupation one of the policing students was able to negotiate with them and say something to the effect of ‘Nah, there’s nothing going on here, these guys are alright’, helping to defuse the situation. The occupiers also found unlikely allies in the campus security, as demands around improved security were part of the Log of Claims. Security would turn a blind-eye to the constant chalking across campus, and at times would unlock the nearby staff showers after-hours and make them available to the occupiers.

‘The unions knew we were true friends’: union and community solidarity

Importantly, the occupation was able to win support from unions, the local community and beyond. Letters of solidarity were sent from at least six unions. Both the Ethnic Communities Council of Australia and the NSW Labor Council passed motions of support. Ghazi Noshie from the Australian Manufacturers Workers’ Union stayed for three 6-8 hour stretches, gave them support during negotiations and even bought 30 AMWU members from a nearby site down to the occupation during their lunch break. Yet this support didn’t come out of nowhere. For the preceding year, NUS NSW and the Cross-Campus Education Network had been mobilizing students for the pickets of these unions demonstrating their commitment and solidarity.

Students from across Australia sent messages of support, as did local businesses Bankstown Auto-Pro and Greystanes Charcoal Chicken. Even the Indonesian National Students League for Democracy heard of the occupation, and sent a message declaring their: hope that this kind of action will spread throughout the country and may the new world revolution start from Australia!

Inspired by this, stickers were produced that read ‘The revolution begins in Bankstown!’.

Life in the occupation

While workers’ councils weren’t formed across Western Sydney, numerous interviewees did attest to an incredible feeling of camaraderie and solidarity in the occupation and how important this was in sustaining it over the 14 days. While there was an informal, predominantly male leadership group, there was an emphasis placed on making the space as democratic and inclusive as possible, which helped facilitate this. Progressive speaking lists were introduced, and key decisions were made at all-in collective meetings. Importantly, politically inexperienced students were encouraged to take initiative. In one passionate, 3 page e-mail to the National Broad Left e-list, Richard Martino stressed on these lines that:

the old myth that you cant (sic) rely on people that have not had the experience in student politics is absolute bullshit. We had students who had never done media releases before in their life doing media releases and interviews. Perhaps the standard was not at the highest level imaginable, but the importance of giving students ownership over building the action was perhaps the most liberating experience for them.

The sense of collective control and power that this process fostered was vital, and this attitude meant the occupiers were hostile to anyone who was seen as subverting this collective process. More generally, most activists remembered it as being a really fun time. For instance, the casual lecturer and fellow occupier Julie Sloggett recalled how:

The night before the occupation started, I don’t know why, I’d gone home and I’d bought these Winnie the Pooh hats. So there was a Tigger hat, a Piglet hat and a Winnie the Pooh hat. And at one point whoever was the speaker had to wear the Piglet hat! So there’d be these really intense, full-on, political conversations going on but the person would be wearing a Piglet hat! So it kind of took the seriousness away from it a little bit.

As the days went by, feelings of camaraderie amongst the occupiers gradually built up. Andrew Viller recalls one incredible story of how:

a really angry aggressive fairly large bloke came at the occupation quite suddenly, and he started ranting that we were disrupting his learning and he didn’t give a fuck about this and that, it was really full on. And he was a big guy and um, Jorge was a Chilean refugee basically, a queer activist, socialist and about five foot tall and he confronted this guy, who just jumped at him and started screaming … And this policing student … who was about six foot four tall stepped in and put his hand around Jorge and basically confronted this massive dude and he says ‘stay away from my mate unless you want some’. Which … shows this real transition – we’re talking about a guy who used to be in the army, was a policing student, was kind of ocker and blokey as they would come, and through the occupation, you know, we’d developed this amazing bond and (he was) protecting this queer small Chilean dude from this really aggressive dude! And then after the moment (he) grabbed the red NUS flag, put it on his shoulder and marched up and down in front of the building, in this act of like, this is where I am and this is where I belong.

Similarly, Sloggett sent an emotional e-mail to the collective titled ‘Solidarity from Within’, highlighting the strength of this bond. It read:

I want you all to know how proud i (sic) am of all of you (and me too!) I feel like i (sic) have been privileged to be a part of this, and to get to know some of you better, to meet some of you for the first time, and to form what i (sic) see as real bonds between us all as a group.

I have been at this uni for nearly 8 years, and I have to say, that this is without a doubt the best thing that has ever happened. If it was up to (me), I would give you all academic credit for taking part – you have displayed all the things that we try to teach you …

Yours in solidarity, respect and i (sic) hope friendship?Julie Sloggett – Official Poster Girl for Funding Cuts Are Us

This sort of connection helped to pose the question of what a different world could look like, and a number of students recalled the occupation as being pivotal in their political radicalisation. Amy McMurtrie remembered:

one day sitting there with a few people and just being like ‘oh my god, everything’s fucked’ and they were like ‘yeah, yeah, yeah, we know’ and I was like ‘No, no, no, you don’t understand, things are really really bad!’ It was just like suddenly my mind was exploding, and you know everything was kind of connected … I just remember that time as this deep kind of opening, of understanding the world in a different way that I never had.

This sense of excitement and possibility ran deeply throughout the culture of the occupation.

The occupation ends: victory for the students

It soon became clear through the negotiations with the university that they were willing to give in fairly quickly to some demands, such as around parking fees, but were much more reluctant to concede others. In particular tutorial sizes and the question of staff cuts were sticking points.

Importantly, the uni was reluctant to resort to the use of police – unlike other universities which had used the cops to clear out occupations to great effect. It’s unclear why – some activists speculated that the admin was reluctant to sign off on something that might lead to arrests and violence as that could tarnish their image in the Western Suburbs. The university was also going through a restructuring process, and there was a lot of tension between the different campus bureaucracies associated with UWS around competition for future jobs. Some of these were strongly linked to the ALP left, unlike David Barr’s more conservative Macarthur admin. The more liberal elements, that were hostile to Barr, may have been particularly reluctant to endorse police action.

The restructuring process may have also influenced the decision to concede to student demands. It was accepted that any agreement would have to be subject to re-evaluation when this came into effect at the end of the following year. A deal was put in place to review the agreement in the first quarter of 2001, with student consultation forums. Therefore the university may have calculated that being bound to an agreement for a short amount of time was a manageable hindrance.

Another factor was NUS’s decision to hold a state day of action at Campbelltown campus on Wednesday November 11. This was particularly significant because of the history of previous NUS action – in 1996 there had been an NUS National Day of Action at Campbelltown, as the university had withheld a lot of student fees that should have been passed on to the union. At a mass demonstration of several thousand, the students had received word that David Barr was in the Law Building, and rushed to occupy the space, kicking in windows in the proces. They held the building for a few hours until the administration caved.

In the leaflets for the day, the activists consciously played up this threat, promising to bring their ‘anger’ at Barr to Campbelltown. This acted as a leverage point against the university, as they were scared of a repeat of 96.The night before the NUS action the uni admin admitted defeat, conceding to 27 student demands. By noon the next day the occupation was over.

‘We know how to do it’: the legacy of the Bankstown Occupation

Although activism at UWS never again reached the highpoint of the occupation the left was galvanized by it, growing considerably out of it. In particular two actions stand out. The first of these was the solidarity shown to workers from the nearby Mirotone paint factory in 2001.

On the 22nd of February that year, the 28 workers from the plant were locked out by their employer. This was following a lengthy dispute over their Enterprise Bargaining Agreement, in which the company had been trying to impose a 38 hour week on the workers, and to get them to sign individual contracts – meaning that the union couldn’t intervene in cases of individual disputes between workers and Mirotone.

In response, the workers staged a sit-in at the factory. As the factory was very close to their campus, UWS students became involved when they noticed the picket on the side of the road. Because of the aid they had received in 1999, they ‘understood the importance of solidarity’ and offered their support. Students began regularly attending the picket lines, bringing down food from the uni cafes. Eventually the student support culminated in a state-wide delegates meeting of several hundred unionists being held in the university bar, which resulted in a fund being set up to support the locked-out workers. On April 2nd, the workers won the dispute, and kept an NUS flag in their lunchroom, in memory of the support they had received.

Even more significantly, from September-November 2001, some of the 1999 occupiers were involved in a 52 day occupation of Goolangullia, the Aboriginal Education Space at Bankstown campus. UWS had planned to end the Indigenous unit at Bankstown and at the other campuses, rolling back the course and centralising everything into one program. John Mcguire – then President of the Students’ Association – and one of his close comrades had gradually developed a friendly relationship with some of the Aboriginal staff and students on campus. Due to their own experience, they suggested an occupation, and one began soon after. But this time the university was much more hostile, cutting the power to the building, refusing to talk to them and sending in an Occupational Health and Safety officer to try and kick them out. At one stage, the students even blockaded the university, trying to shut it down, which was relatively successful. Eventually their persistence won out and the university came to the table, conceding to their demands. The Bankstown course remained, and it continued for the next 15 years.

Conclusion

One shouldn’t romanticise the 1999 occupation, and it’s easy to lose sight of the limits of the demands in terms of their scope and duration. Amy McMurtrie recalled, for instance, that at times the occupation’s informal leadership ran counter to a democratic culture:

whilst I think there was a level of democratic process, there was also a level of more experienced people calling the shots … I had a sense that there were these kinds of caucuses happening around the space, that I wasn’t a part of, and that was frustrating, that did seem like a level of kind of hierarchy that I couldn’t quite access

It’s also easy to fetishise the Log of Claims as a tactic because of its success. Specific problems with a Log of Claims can arise – for instance it can rapidly become a long list of demands that looks as impossible to achieve as a demand for instant revolution. One can also overlook the role of patient organising and leap ahead to the thrill of an occupation. While Bankstown does suggest the importance of certain principles, in particular genuinely collective organising that fosters a sense of ownership, and the potential use of strategies and tactics like the classroom delegate system and the focus on winnable demands, it is therefore perhaps better to remember it as an injunction to think creatively about how to organise patiently, imaginatively and carefully, rather than as a model to be uncritically replicated.

The occupation was clearly a moment of incredible exuberance, joy and energy. For Karen Hooper it was ‘a really important time in my life’, expanding her political horizons enormously in just 14 days, while McMurtrie eloquently described how:

most people there had never experienced anything like that. There was a real sense of that we owned the campus. So I don’t know what it’s like now, but the Student Centre was in the middle … most people had to walk through there, to go anywhere … There was a sense of, we really did feel like we were in control, that students were in control … there was such a sense of momentum, that things were really going somewhere, that we were powerful

While of course the feeling that ‘we owned the campus’ was a temporary one, and the demands won by the occupiers were gradually stripped back, a moment that illuminates a counterhistory of the modern university, as well as how rebellion can be joyous, inspiring and fun, not based on guilt, sacrifice and responsibility seems worth remembering – both as history in its own terms and as a way of pointing towards political possibility. It is part of showing the lightness and joy of being communist.

–

Tim Briedis is a historian and anti-capitalist. He is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Sydney, and is researching student protest and activism in Australia after the end of free education.

Join us for a panel discussion on student activism and the Bankstown Occupation on Wednesday 23rd September 2015 10:30am at Bankstown Campus.